In 1988, Jörgen Schmidt-Voigt, a German doctor and collector, brought about 800 icons to Frankfurt which were later moved into the Museum of Icons. After reopening in 2021, the Icon Museum in Frankfurt presents its permanent exhibition which collects the icons and sacral heritage from Russian, post-Byzantine, Italo-Cretan, Romanian, Scandinavian and Ethiopian cultures.

By Hanna Vasilevich

Pictures: Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt

The exhibition in the Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt numbers around 130 items among which are icons and wooden and metal liturgical utensils placed in a two-storey room painted in red. The choice of the wall colour can be explained by the symbolism of red as the blood of Jesus or a delightful event such as the day of the Resurrection. The major goal of the exhibition is to give visitors a deeper understanding of the global orthodox heritage that has been gathered since the 16th century. The setting of the exhibition does not reflect a particular order or chronology. Most items and icons are grouped into thematic concepts: episodes from the New Testament, images of Jesus Christ, the Mother of God (the Virgin Mary) and other saints.

An icon or a painting?

An icon is regarded as a sacral, canonical image of Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, the Holy Trinity, saints, and other significant sacral events. Icons originally represented an Eastern Orthodox tradition. Every element of the icon, including the holy face, position, and movements, has a symbolic value. For example, large eyes symbolise access to God’s mysteries, thin lips asceticism, raised hands a prayer, and a hunched posture humility.

What are the main differences between an icon and a painting? An icon, as opposed to a secular painting, serves as a direct connection between God and a human being. It also has more sacral and testimonial purposes. Whereas a painting can impact the human mind in both positive and negative ways (for example, E. Munk’s »The Scream«), an icon is only directed to a positive purpose through the contact between a prayer and a certain saint. Even though an icon artist will unavoidably reflect their unique style and interpretation of the things or events they depict, Orthodox tradition stipulates that specific approaches be used in order to avoid misrepresenting God and the sacred figures. Last but not least, each icon goes through the blessing-like process known as consecration. However, the criteria and conditions for the icons to get consecrated are establish by the Orthodox church such as a depiction of nymph overhead to show sanctity and the saint’s name inscription.

Nowadays, it is possible to observe icons and discover their history by visiting a museum. Nevertheless, is an icon still considered a sacred image or is it more of historical heritage? Can they still serve their purpose? Can an icon be placed in a church even though it has some mismatches with the Christian canon?

Is it Orthodoxy?

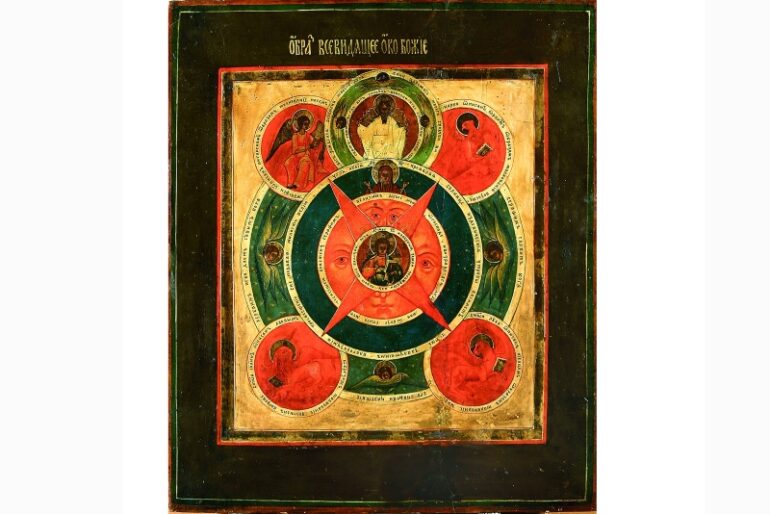

Russia, 19th century

Egg tempera on wood

The icon »The All-seeing Eye of God« has belonged to the Russian Orthodox tradition since the 19th century, however, it is hard to find it in churches nowadays. The icon originally came from Old Believers, an alternative branch of the Orthodoxy which opposed the unification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the Greek Church. As can be seen, it depicts the all-seeing eye of Christ in the image of Emmanuil in the middle, as well as the Virgin Mary and God. Circles represent the motif of the eye as a symbol of eternity. All-seeing eyes convey the message that no one is forgotten: God cares about everyone. The eye itself was a popular motif on Old Believers’ icons which starting from the 18th century was borrowed by the Orthodox Church and became a symbol of the Holy Trinity as well as of numerous pieces of architecture, such as the Kazan Cathedral. Thus, the Russian Orthodox Church is rather sceptical about the icon and considers it non-canonical.

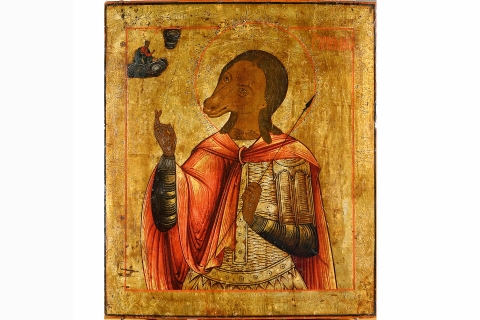

Russia, around 1850

Egg tempera on wood

Another outstanding example of the Orthodox, as well as Catholic tradition, is the icon of St. Christophoros Kynokephalos. The arguable and provocative element of the icon is, apparently, the head of the dog (or sometimes the head of the horse can be depicted), which made the icon proscribed by Russian Orthodoxy. Originally, the image of Dog-Headed Christophoros was discovered between the 6th and the 7th century in Macedonia. The dog’s head is a subject of several existing legends: one of them tells that a dog-headed human came from an image of people living in the areas of India, Africa, Scythia, Libya and Ethiopia who were considered alien to locals. The icon of St. Christophoros Kynokephalos was respected in both Eastern and Western Christian traditions. However, starting from the 18th century the clergy spoke out against the depiction of an animal-like man, which led to the correction of the head into a human-like shape.

The icon itself evokes contradictory feelings as it dramatically differs from the regular icons with regular human bodies of saints. A dog-headed saint stands out or even frightens and tears away. Nevertheless, for a long period of time, the icon was used to help people to fight illnesses, weaknesses and devil obsession. Moreover, Old Believers are the ones who still respect and worship the icon.

Russia, 19th century

Egg tempera on wood

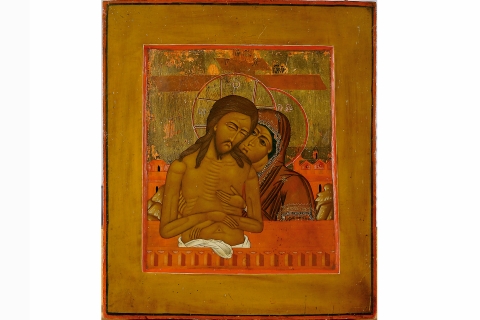

What instantly catches attention when one looks at the icon »Don’t Cry for Me, Mother« is the image: the Mother of God is depicted with Jesus Christ being an adult and, what is more, being dead. However, the fact that Jesus is half-hidden in the coffin which reveals his triumph over death. His head inclined down symbolizes the descend into hell and the deliverance of people’s sins. The title of the icon is the second feature that grabs attention. »Don’t Cry for Me, Mother« is a line from the ninth song in the Canon of Matins that is related to the following New Testament episode:

»Weep not for me, O Mother, beholding in the sepulcher the Son whom thou hast conceived without seed in thy womb. For I shall rise and shall be glorified, and as God I shall exalt in everlasting glory those who magnify thee with faith and love«

the Canon of Matins

It portrays the scene of Jerusalem’s women beginning to weep as Jesus Christ is approaching Golgotha. He warns them, however, to weep not for him but for their own sons because they reject him as the Messiah and put him to death. The Mother of God cannot help but mourn; meanwhile, Jesus consoles her by saying, »Don’t cry for Me, Mother« because he will fight death. Thus, the icon itself is particularly appreciated on Good Friday when Orthodox people are praying for consolation and strengthening of their faith. Russian poet Anna Akhmatova mentioned these words in the poem »Requiem« portraying the tragic process of the crucifixion of Jesus:

A choir of angels glorified the greatest hour,

The heavens melted into flames.

To his father he said, »Why hast thou forsaken me!«

But to his mother, »Weep not for me…«

[1940. Fontannyi Dom]

translated by Tom Clark

A Museum of Icons – worth visiting?

The Museum of Icons is for people who have any interest or curiosity in discovering the unusual side of Orthodox iconography. The exhibition allows getting familiar with sacral utilities and rare icons untypical for the Orthodox tradition. Whether rare and valuable icons and sacral utilities should be preserved in museums or should be kept in churches and serve their purpose is a matter of debate. It was and still is an important question, especially concerning the Eastern Orthodox area: a balance is needed to be kept between museum and the church in order to follow the same goal – spiritual enlightenment and preservation of Christian heritage.

The Museum of Icons in Frankfurt unites people from different cultures as icons are collected from all around the world demonstrating that Orthodoxy comes not from a particular area but many different spots in the world.